After a long and tiring school day, a little boy who struggles to move his body wraps an arm around his big, fluffy Labrador and they walk together toward his bed. Without the dog’s help, the boy would have to rest several times during this short journey. With big brown eyes, a wet and cold nose, and a furry tail that wags in excitement at the prospect of assisting someone, service dogs make the difference for people challenged between living a mobile lifestyle and being overburdened by a disability or disease.

There are hundreds of organizations in the United States that train assistance dogs to help people with various disabilities or ailments. Some of these groups breed their own dogs, and others train personal pets. It takes roughly a year and a half to raise and train rambunctious puppy into a full-size, obedient dog. Most pet parents wouldn’t be in any hurry to return the newly-trained dog back to the organization it came from. But that’s how most service animal organizations operate: volunteers receive puppies to train and socialize, and after a year to a year and a half the dogs go back to the organization to complete their training. Upon returning the dogs enter intense training to learn specific tasks, such as door opening, pulling and picking up objects. Professional trainers then perform behavior, temperament and health evaluations to get to know the dogs and figure out who the dogs can help.

Most service animal training programs provide dogs to people for free, assuming the individual can demonstrate that an assistance dog would increase their independence or improve their quality of life. Some organizations specialize in a particular type of service dog. For example, Guide Dogs for the Blind trains only guide dogs. But some groups, like Canine Companions for Independence, train for a myriad of services, including hearing, various physical, cognitive and developmental disabilities, and therapy and facility dogs.

The relationship between humans and dogs has long been known to have benefits other than just a reason to get out the door to go for a walk. Dogs in particular are known for their unconditional love toward humans, and their ability to calm people just with their presence. A study from the University Hospital of Wales about the benefits of pet-facilitated therapy showed that simply petting a dog can lower a person’s blood pressure. Another study by the American Psychological Association proved that the presence of a pet dog provided “non-evaluative social support” which lowered the effects of stress on the participants.

As anyone with an obvious physical disability knows, stares from the public and awkward interactions are all too common. Although bringing a dog into a grocery store or to a restaurant will also garner intense stares, the dog is an icebreaker and a way to turn the focus off of someone’s disability. Having a service dog builds their confidence to go out in public and that people will address them and their dog, not their disability, says Amanda Wolf. Wolf is an apprentice instructor with Canine Companions for Independence, a non-profit organization that raises service animals. Kids like to show off their dogs, again diverting attention from a wheelchair or any other mobility equipment they may use.

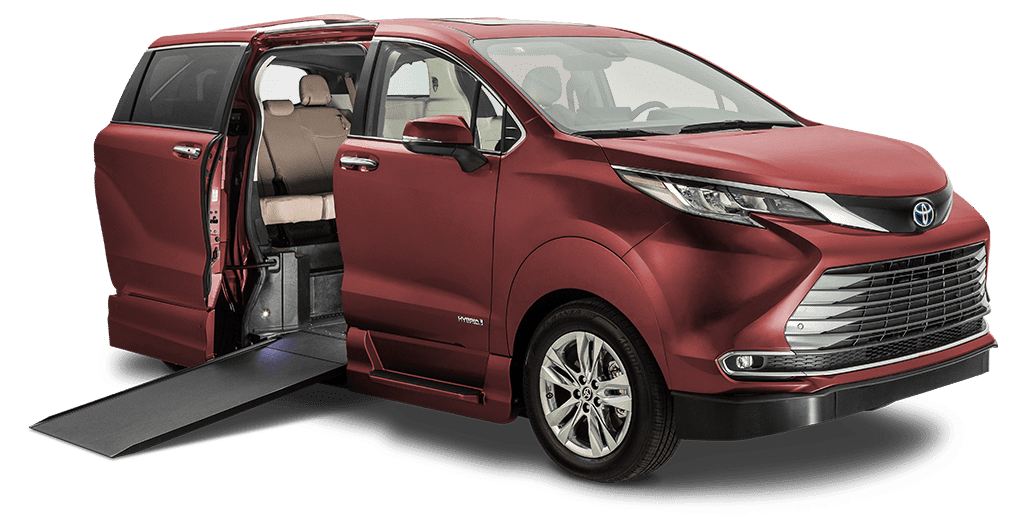

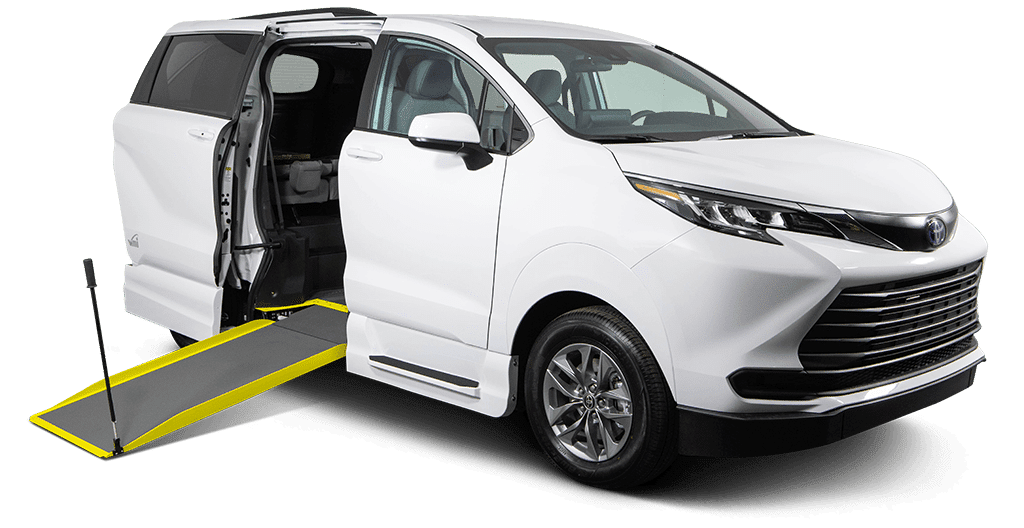

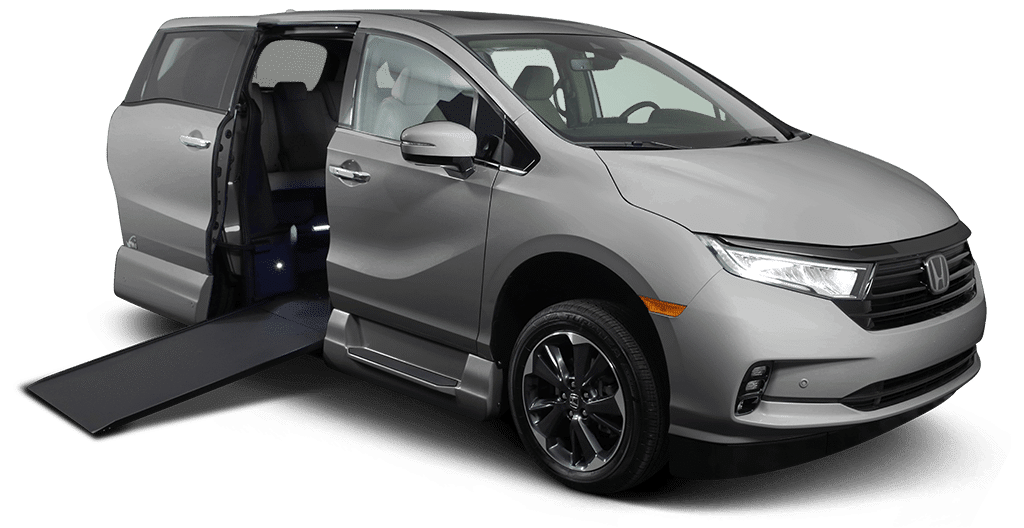

In most cases, a family member or a paid caregiver will assist someone who has limited mobility with daily tasks, transportation via a handicap van and errands. Especially when the individual needs considerable help, it’s easy for them to feel dependent on their caregiver, which can feel burdensome. With an animal assistant, that’s rarely the case. People with service dogs self-report that they feel more independent, and have increased confidence in their ability to live their life, says Brian Ogle, an anthrozoologist from Beacon College in Leesburg, Fla.

The attachment that people feel toward their dogs, paired with the pleased-to-serve attitude of most dogs, means that asking an assistance dog to turn on a light, pick up a dropped pen or alert them to doorbell sounds won’t be embarrassing or a source of shame. Having a constant source of help and support gives people a sense of confidence, safety and reassurance that if something happens while they’re out, they can handle it on their own, Wolf says.

These days, dogs aren’t the only option for service animals. Monkeys, horses, boa constrictors, parrots, llamas and pigs are all options when it comes to non-canine assistance. Dogs are far and away the most popular choice for a service animal. They’re the most practical for traveling purposes, the most commonly seen in public, and most importantly, very trainable. (They’re also the only animals protected under the Americans with Disabilities Act. Some other service animals, such as miniature horses, have been grandfathered in to also be protected.)

Dogs were the first domesticated animal, their wild ancestors manipulated into the dogs we have today, and humans’ influences on them has become part of their genetic makeup, Ogle says. Plus, dogs are willing to be around and engage with others, arguably the most important aspect of a working animal whose job is to be in public.

With organizations around the country providing dogs with all sorts of skills to those who need them, a service dog can be a legitimate and helpful replacement for a human caregiver. And even better, science backs it up, showing that dog really is man’s best friend.

For more caregiving information visit VMI’s caregiver resource center.