Larry Watson parked outside the high school gymnasium and football field in Missoula, Mont., where he played just three years earlier, and screamed unintelligibly at God for allowing this to happen to him.

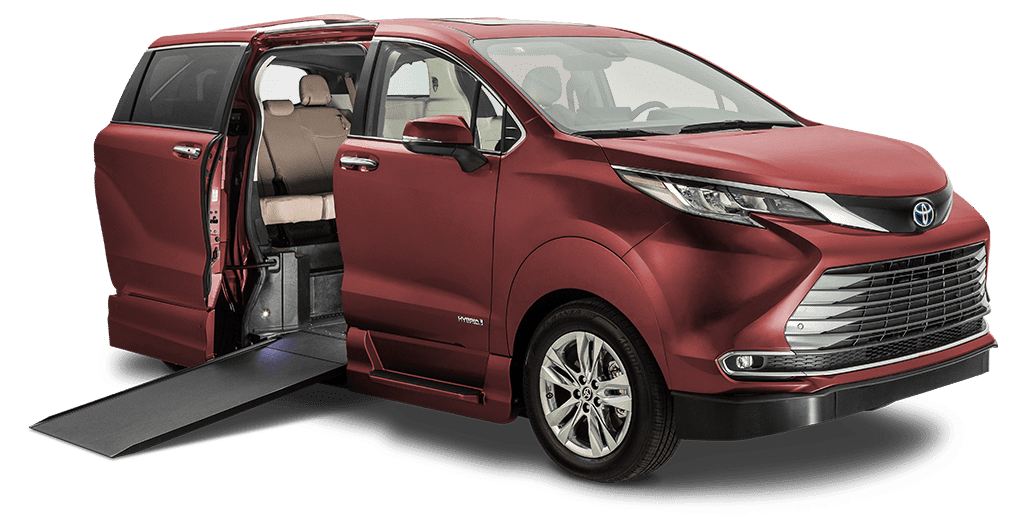

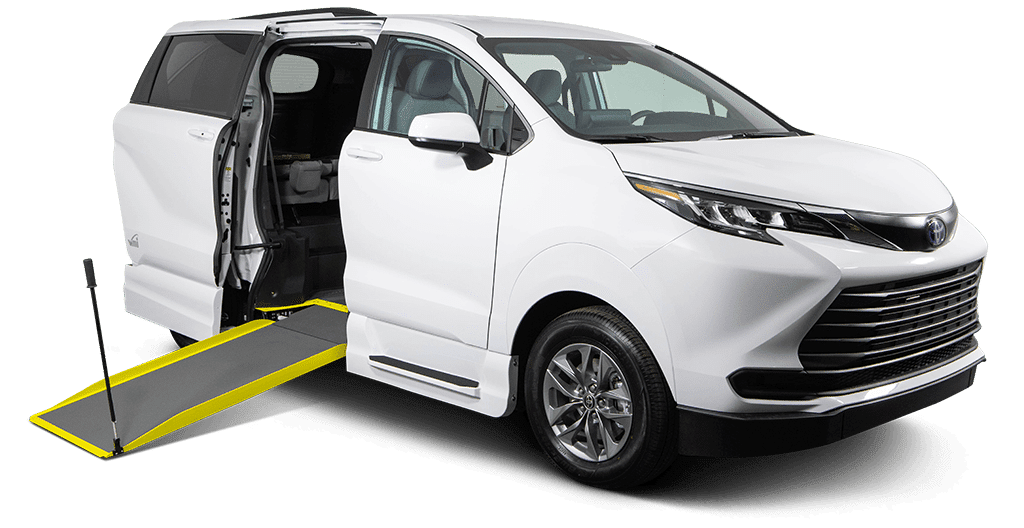

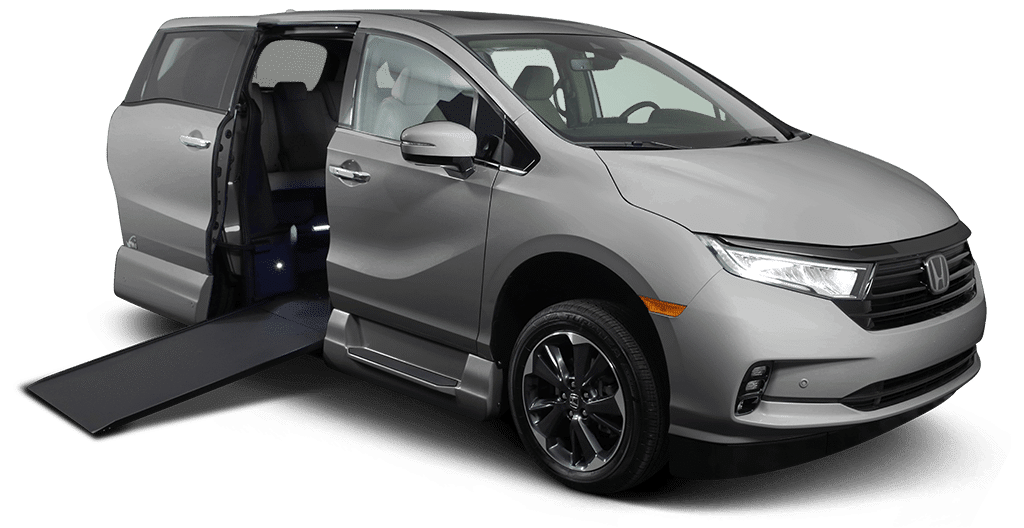

“Why me?” he yelled openly. Nobody could hear Watson’s anguish; only his wheelchair and an adaptable wheelchair van kept him company in the parking lot. Tears gushed down his face and snot freely flowed as he sobbed, “Why would this happen to me?” –– the end-all, be-all question for anyone who has experienced a traumatic, life-changing injury.

He vented his frustration, unaware that in this moment he was finalizing his grieving process. “A soft voice came to me and said, ‘Why not you? How are you any better or any different than anybody else?’” he says nearly thirty years later when remembering the experience.

Watson is a quadriplegic who was lucky to gain some mobility post-accident. He wheels around in a manual wheelchair, works as a successful lawyer and has been married for nearly 30 years. He’s adjusted and made a life for himself, and while he says he’ll probably never get over the “what if it hadn’t happened” question, he says he’s done grieving.

“From that day forward, I moved on,” he says. “Random things happen to people. What makes me so special that maybe I shouldn’t have been injured because I was out on an icy road and we hit a pothole? Bodies are frail. It happens.”

Dr. Beth Sikora is an Arizona-based psychotherapist and licensed professional counselor who in-part works with patients who have mild traumatic brain injuries. She says the process of transitioning into a wheelchair after losing body mobility is similar to grieving someone’s death.

“They may realize they’re feeling a loss of what they had hoped to be able to do,” she says. Shock, denial, anger, and depression are all common emotions wheelchair users can experience before reconciling with what happened and accepting their new, altered life, Sikora says.

Watson, who wanted be a basketball coach before his accident, echoes this concept of loss. “It was basically grief recovery because you’re mourning the loss of what you were and what your life was like beforehand with regards to how it is that you lived,” he says. “I was a basketball player … that was my life, and all the sudden, that was gone. So I mourned that.”

It’s important to note, however, that not all grieving processes occur in the same order and regardless of what causes the grief, we may repeat the process or flip-flop between various emotions before coming to acceptance.

Some wheelchair users will find they don’t experience difficulty when transitioning into a wheelchair, like Emily Ladau, a blogger who founded Words I Wheel By.

Ladau was born with Larsen Syndrome, a genetic joint and muscle disorder that affects her quadriceps. She used a walker and braces to get around in her early childhood before receiving a wheelchair in third grade. In high school, she transitioned to the chair full-time.

“A wheelchair is really my version of freedom,” she says. It’s “something that is very much a part of me even though it doesn’t define me. It’s how I get around.”

Ladau’s peers never made fun of or harassed her because of her chair; for that, she says she feels she’s a fortunate exception to the norm. But what stings, she says, is the sympathy she receives from onlookers.

“You get comments like, ‘Oh, that’s so unfortunate,’ or, ‘Oh, how difficult that must be for you,’” she says. “I know it’s just humans trying to relate to one another … (but) a lot of people see mobility issues and disability in general as being this really tragic thing, when for me, it’s just my reality.”

Negative public perception can cause wheelchair users to feel shame; realizing that society unfairly judges people with disabilities is something they work through on their journey to self acceptance. “Shame is about ‘There’s something wrong with me,’” Sikora says, when the focus should be on how to better educate people passing judgement.

Eric Kenning is the development director for Arizona Spinal Cord Injury Association and was a two-months premature, breech-birth baby born with a spinal cord injury. Similar to Ladau, he walked in his childhood and transitioned into his wheelchair in college where he studied psychology.

Kenning lists myriad emotions he deals with as a result of his injury, but nothing is more telling of his frustrations than the time he intentionally ran into someone with his wheelchair at the mall.

He was sick of people feeling sorry for him and not holding him accountable. To prove the norm that society gives people with disabilities special treatment, he told his friends he could very obviously wheel into someone and have that person apologize to him, despite it being his own fault. He did exactly that, and he was right.

The same lack of accountability plagued his elementary schooling, where he says he felt teachers passed him through the system to get rid of him, even when he didn’t do his homework.

“That’s where some of the bitter hatred comes from,” Kenning says. “If society doesn’t (care) about you … what am I supposed to do? How do I measure up? It’s self confidence (that is affected).”

Sikora says a healthy mindset for wheelchair users doesn’t mean they have to be happy about their situation; in fact, they may never look at their injury or disability pleasantly, but they should aim to stop judging themselves, understand it’s not their fault and rather than think about their setbacks, “work to identify their progress and strengths.”

Watson grieved for three years before he was ready to move on, and he says fully engaging in the process is what led him to acceptance. “I fully felt it. I fully engaged in it, and fully vented it,” he says, “but then when it was over, it was over.”

Other wheelchair users, like Kenning, may adhere to a list of stress-reducing tactics:

- Resiliency therapy is all about staying present, Kenning says. By leaving the past in the past, he says he feels less depressed and more optimistic.

- Mentally preparing for potentially stressful situations

- Communicating difficulties isn’t always easy, Kenning says, but he keeps a trustworthy friend group around whom he can talk with about anything.

- Socializing with people who understand disability but don’t necessarily have a disability is a technique that Kenning says has helped him adapt; Watson, on the other hand, says meeting other wheelchair users with adapted lifestyles influenced him to take charge of his own life.

Watson and Kenning both say having support groups were instrumental in gaining self-acceptance. Wheelchair users in need of emotional assistance should consult with a psychologist, counselor, peer mentor or support group to devise strategies to overcome the emotional hardships of being in a wheelchair.