To skip the full story and get straight to the tips, click here.

—

“I spent the first six years of his life, quote on quote, trying to ‘fix him,’ when there was really nothing wrong with him to begin with. I was the one who had the problem.”

—

It takes a strong person to willingly admit and expose their errors in thinking. As the mother of an 18-year-old son, Robert, who was born with cerebral palsy, Laura Knight has had plenty of time to reflect on what it’s like to raise a child with CP.

Robert and his twin sister, Madeline, were born three months premature; the idea they would have some type of disability didn’t come as a complete shock to nurses and doctors.

But Knight and her husband, Stanton, had been unsuccessfully trying to get pregnant for three years. They used in vitro fertilization to conceive Robert and Madeline.

The couple spent what should have been the most joyous first week of their twins’ lives in hospital hallways praying their babies would survive.

“We would have silly conversations like, ‘Oh, what if she grows up to be this? What if she grows up to be that?’” Knight recalls. “We had this perfect relationship and this perfect marriage, and you think you’re going to have this perfect life…We just could not wrap our heads around (the fact that) this was happening to us.”

Robert’s muscles were so stiff and tight that nurses stuffed towels between his tiny thighs to pry them open.

Knight says she’s glad she didn’t understand the gravity of the situation back then.

Doctors couldn’t officially diagnose Robert with CP because he was too young, but all signs indicated it was a serious, if not definite, possibility. They were right.

Denial. Grievance. Acceptance. A Cerebral Palsy Journey.

—

“I felt like if my faith was strong enough and (if) I prayed hard enough, (then) everything was going to work out. Little did I know, it (would) work out…it is the way it’s supposed to be.”

—

Knight took her twins to church and playdates and lived as though Robert were perfectly healthy.

Until he turned three.

By then, the differences in growth were undeniable. Robert couldn’t speak or walk. Knight’s denial was “painfully obvious” to those around her, she says, but she still didn’t want to believe it.

She avoided interaction and kept to herself. At home she wasn’t forced face-to-face with the certainty that cerebral palsy made Robert different.

Knight says she became “the mom who tried everything.” There wasn’t a physical therapy, speech therapy or occupational therapy session Robert didn’t try. They went on countless trips to the doctor and visited “every leading specialist” they could find, she says.

The doctors’ responses?

Go home and love your child. He has cerebral palsy.

Finally, one doctor made a statement that shook her to the core.

“He said to me, ‘Stop trying to fix him. (In the future), he’s going to think, ‘What was wrong with me that my mom kept taking me to all these doctors?’’ And that hit me hard,” Knight says.

Robert’s sentiments echoed those of the doctor’s when he entered first grade. He begged and pleaded to stop using his walker and transition to a wheelchair full time.

Knight says she and her husband were stuck on wanting Robert to walk, and she even convinced herself that her son’s love of sports would be his motivation to learn.

“We kept pushing, but my son is everything he’s supposed to be,” Knight says. “He’s following the plan. He’s right where he’s supposed to be.”

If she could have fast forwarded 10 years, then she would’ve known she was right, but in a different way. Robert’s love of sports would eventually do him wonders.

Growing up. Transitioning. And the Challenges Associated with CP

Robert is in a wheelchair full time and has proven himself to be a valuable asset on school sports teams.

In seventh and eighth grades, Robert managed the school’s basketball team; his freshman and sophomore years of high school, he switched to managing the baseball team. His junior year, the family moved from Phoenix to Nashville, and he volunteered in any area of sports he could. Now a senior, he calculates statistics for the basketball coach and works as the head football coach’s assistant.

In the future, Knight says Robert speaks of becoming a minister and reporting sports news for ESPN.

“He’s the neatest kid,” Knight says. “He just goes for it.”

But Robert has had his share of struggles along the way.

Moving states and growing up

Robert has moved states three times with the family, and Knight says unfortunately, each move gets a little harder.

“Anytime we would move, it would creep up again,” she says. They had to repeat the process of making friends, explaining why he was in a wheelchair and finding kids who accepted his differences.

The move to Nashville was probably the most difficult. “You almost have to work a little bit harder when you’re that kid in the wheelchair because by the time you’re in high school, people don’t know what to say,” Knight says. “He has to really make an effort to put himself out there… (but) he never misses a beat.”

CP has also brought new meaning to typical teen experiences.

Knight recalls one particularly heartbreaking memory when Robert mustered up the courage to ask his crush to the homecoming dance. She said yes, only to take it back the next day, saying she had family plans she had forgotten about.

Robert was devastated, she says, and he blamed CP for why she backed out. Knight was quick to respond, though, and she told him, “Honey, girls are girls. She may not have wanted to go with you because you’re in a wheelchair, but it might have been because you have glasses. It might be because she doesn’t like blonde boys … Girls are girls.”

Regarding maturity and CP, Knight seems to have an enlightened way of understanding.

“As kids are growing up in middle school and high school, it’s just a hard time in life anyway,” she says. “The more we can do to make our kids comfortable with our differences, the better off our kids are going to be.”

Growing out of the Wheelchair

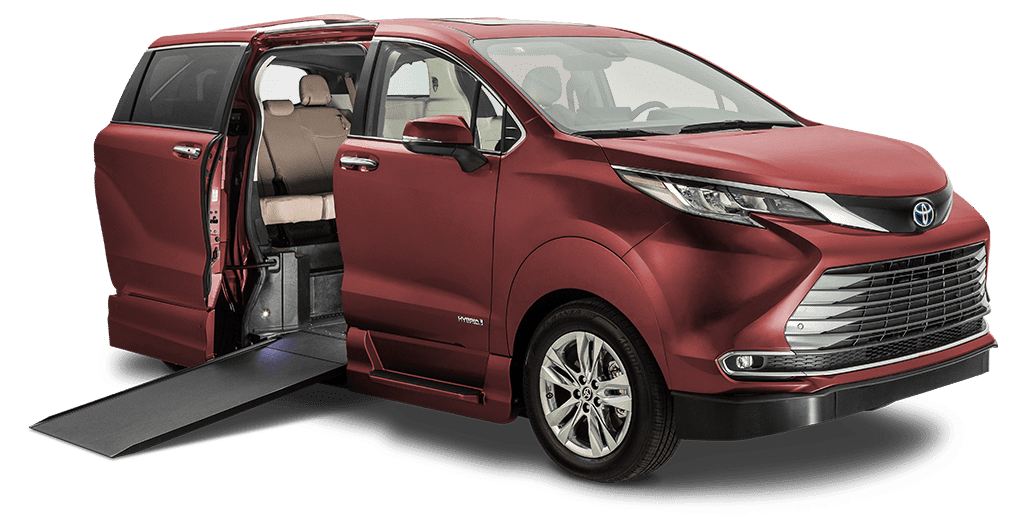

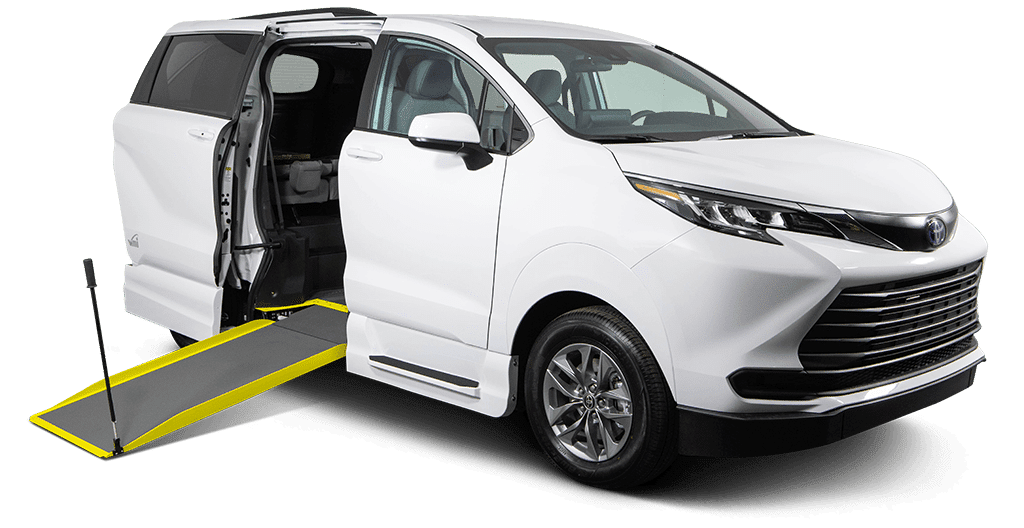

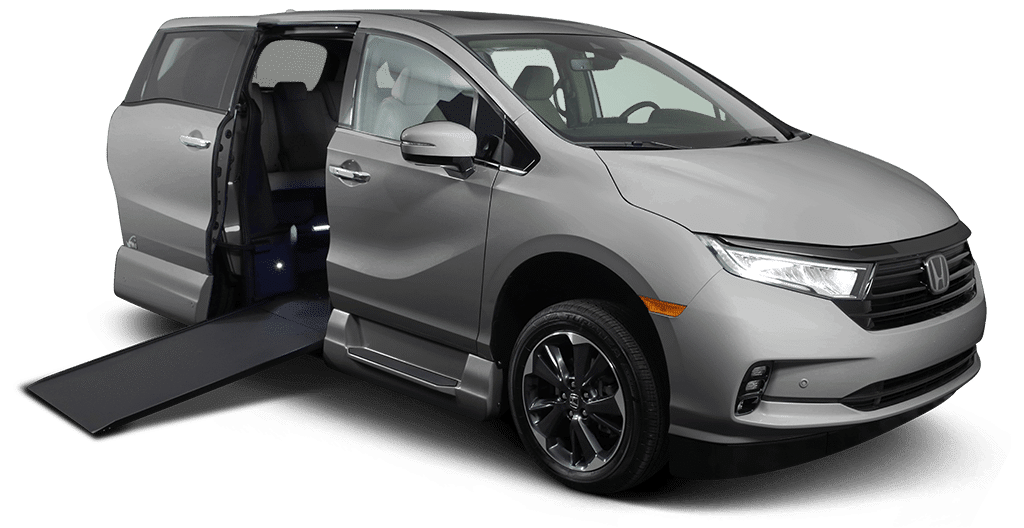

The wheelchair process can be “daunting” and “frustrating,” because there are so many steps and factors to consider before choosing a chair, Knight explains. One of those factors includes choosing a chair that will collapse and fit into a car for families who don’t own wheelchair vans or wheelchair lifts.

Dave Thompson, a seating specialist for NuMotion, a mobility product and service company, says wheelchair manufacturers today are focusing on longevity and how to create wheelchairs that last up to five years. Robert is 18 and has already gone through five.

Longer-lasting chairs will combat the costly nature of the products, which Thompson says can be around $2,500 for a basic-level chair for people with CP. They increase with complexity and can range between $6,000 and $9,000 or more.

One of the most popular choices for children with cerebral palsy (one that Robert has used, as well) is the growth kit, Thompson says. The growth kit makes chairs expandable for when children grow larger. Some kits allow chair frames to expand by 2 to 4 inches.

Other options include allowing room for growth. Thompson says certain wheelchair components have to be exact measurements for safety reasons; for example, the headrest and footrest. But he says sometimes, seating specialists can allow an extra inch on each side of the seat for children to grow into.

The Unexpected Joyful Days of Cerebral Palsy

—

“This is who you were meant to be. God doesn’t screw up. He didn’t mess up on you; you’re not damaged goods. You are part of God’s plan. I think teaching my son that gave him a lot of confidence.”

—

One year Robert ran for student body president. When he made his speech in front of the audience, he said something no one expected.

“I really think I’m pretty good at solving problems,” Knight remembers him saying. “We’ll try to figure it out together, and if not, then I’ve always been pretty good at rolling with it.”

Everybody burst out laughing. Knight says jokes like this aren’t unusual for Robert and their family. They’ve learned to make light of what they can and laugh whenever possible.

Knight’s Inspiring Advice for Parents of Children with Cerebral Palsy

—

“It’s okay to feel the way you feel. It’s okay to be angry; it’s okay to feel guilty. Don’t ever stop fighting for your child.”

—

There have been times when Knight was asked to help other parents who recently discovered their child has CP. Though always willing to be there for moral support, Knight says the biggest lesson those parents have to learn is they are on their own journey.

No two people react the same way, she says, and everyone experiences unique feelings specific to their situations. Go through the emotional journey, Knight advises; be shocked, sad, angry, or whatever other emotion you need to feel, and then accept it.

Her second biggest piece of advice comes from a decision she and Stanton made early on. They decided to teach Robert that it’s okay he is different, and that it’s okay for people to be curious.

“People are going to look at you; people are going to point. They’re going to ask questions,” Knight says. “Answer them. That’s the way we learn!”

The decision to be outwardly open about Robert’s CP also helped her and Stanton tighten the reigns when it came to their son’s education and social skills. There was a time, she recalls, when he needed serious disciplining, but because he had CP, she found many family members, friends and even school teachers gave him a pass. She and Stanton, however, maintain that they have very high expectations for Robert.

“We want to make sure that people know, you don’t get a special break because you’re in a wheelchair,” she says. “You still have to follow the same rules. I expect him to go to college and move out of my house someday.”

Above all, Knight emphasizes how teaching openness has made moving and switching schools easier for Robert, his classmates, his teachers, and herself and Stanton.

Takeaway Tips for Raising Children with Cerebral Palsy

1.] Let yourself feel your emotions. It’s okay to feel angry, upset, scared or guilty. Living through the tough beginnings will allow you to get through to a happier, more peaceful side.

2.] Recognize CP is not always to blame. Robert blamed his homecoming date ditching him on CP, but Knight reminded him: it might not have been because the wheelchair. “It’s because girls are girls.” There are plenty of other reasons.

3.] Encourage your child to get involved and enjoy life. Robert always loved sports. Although Knight originally hoped it would motivate him to learn to walk, she now sees it has given him other sports managerial and leadership opportunities.

4.] Be patient during the wheelchair process. There are many factors to consider and many steps before actually receiving the chair. Try to take a deep breath and remember everything will work out. If possible, try to keep a backup chair available.

5.] Be open about CP. Being open and willingly explaining CP, and how it affects Robert, has helped the Knight family in nearly every aspect of their lives. Knight emphasizes how being open can help spread awareness and promote understanding, which leads to acceptance.

6.] Keep expectations high. Knight says she and Stanton are strict with Robert and expect him to succeed in life. He has challenges most people don’t, which she says they understand, but they won’t let those challenges keep him from achieving his dreams.